Article reproduced by kind permission of RnR Magazine. It appeared in the May/ June 2022 edtion.

Remembered by many for their arrangements of ‘Blinded By The Light’, a chart hit in 1976, ‘Davy’s On The Road Again’ and ‘Mighty Quinn’, Manfred Mann’s Earth Band have, since 1971, toured Europe, the UK, USA, Russia and Australia, performing more than eighteen-hundred gigs, recording seventeen studio albums and releasing thirty-seven singles. From 1996, they have toured every year, until the Covid pandemic cut into what was their fiftieth-anniversary year in 2021.

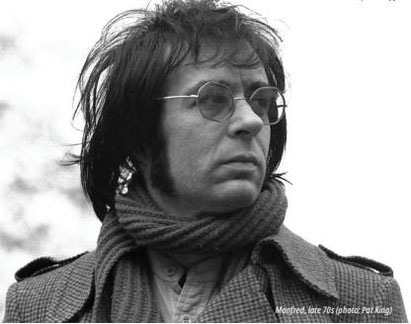

The band now have gigs scheduled for 2022 so when I spoke with Manfred via a video call, I asked him how he felt about going back on tour. “In many ways, I’m looking forward to playing and seeing the guys again but I haven’t done a gig in almost two years. I don’t know how I’ll feel.” Manfred lives in Sweden where almost nobody knows him as Manfred Mann. He is very protective of his privacy. Born Manfred Lubowitz in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1940, he came to England in 1961 to escape apartheid and to make a living as a jazz musician. He had played piano from an early age and, after leaving high school, gigged part-time though not professionally. In the three years before he came to England, he worked in his father’s printing business, which is where he thought up the name Manfred Mann.

“I can almost see it now. I was cutting some paper, and thought ‘Lubowitz is just the wrong name’ [for a musician]. Manfred Mann is my professional name – it’s not my personal name. My friends all know I’m not Manfred Mann. I’ve always known who I am.” This last comment gives an insight into the man and his career. The music scene in 1960s London gave him the opportunity to help shape the Manfred Mann band, which was competing with The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Who at making hit records.

Manfred told me, “I went from playing [jazz] piano to playing organ in the 60s band. Once we were making records, I ceased to be a keyboard player. We were a record-making machine. That was the idea and we did it very successfully.” However, as a musician, Manfred needed to find a different type of success. He broke up the Manfred Mann band in 1969 and formed Manfred Mann Chapter Three, which included a brass section, and attempted to return more to jazz. “For me, as a musician and keyboard player, it was much more satisfying to be able to be what I was when I was eighteen years old.” But in 1970 there were not enough people wanting to listen to that type of music. So in 1971, he joined with Mick Rogers on guitar and vocals, Colin Pattenden on bass, and Chris Slade on drums to form Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. So, I wondered, where did the name come from? “To me there was something about the play on the words Mann and Band that I liked. Earth Band has an ecological ring about it and it doesn’t sound too pretentious.” There have been a total of twentyfour musicians in the Earth Band, with Manfred himself on keyboards and vocals the only constant member. Mick Rogers left in 1976 and re-joined in 1983. With Manfred and Mick in the band today are Steve Finch (bass, 1986, then since 1991), John Lingwood (drums, 1979 to 1987 and since 2016) and singer Robert Hart (since 2011). Looking back at the fifty years of the Earth Band, they are known particularly for their live performances so I asked Manfred about this. “We are good live. Sometimes I see us at a festival with 15,000 people. We don’t draw 15,000 but people are there and they get a feeling that these guys know what they are doing. It’s hard to explain but eventually people are drawn in because it’s actually working.

Something is happening that I can’t put my finger on. Maybe it’s the arrangements when we play live. We’re good musicians. We’re not the best musicians but something happens. There is a kind of magic about that small element of it. “When we are performing, there are certain tricks I have. People should be able to hear what you are playing. If Mick’s playing a guitar solo, I’ll play behind him as little as I can, so I don’t cloud what he’s playing. When I’m playing, he sometimes stops for ages to give me space. So when you hear us play then generally you hear immense clarity of sound.” Are there any songs he likes playing best? “Well, I can’t think there is a particular track but I know there are sections of tracks. Sometimes they come up and I think, ‘I can play this for years.’ We do a funky intro to ‘Mighty Quinn’ and I love playing that. It’s very loose and very ad lib. You can do anything but it’s with a cool groove. I like funk and groove. We’re not known for that but it’s what I like playing most. And actually I’m quite good at that but I’m not known for it. You become known for the successful records.” The successful records for the Earth Band began in 1973 with ‘Joybringer’, an arrangement by Manfred with lyrics by the band. It was based upon the ‘Jupiter’ theme from Holst’s The Planets suite. This was still in copyright and so Manfred had to get permission from Gustav Holst’s daughter, Imogen. She had said ‘No’ to many previous requests but after hearing the song she agreed. Their next and biggest hit, ‘Blinded By The Light’,

was a rearrangement of a song from Bruce Springsteen’s first album. Then came ‘Davy’s On The Road Again’, Manfred’s arrangement of a song co-written by Robbie Robertson. Added to these are their rearrangements of two songs from Bob Dylan, ‘Father Of Day, Father Of Night’ and of course ‘Mighty Quinn’, a much rockier version of the Number One hit record of 1968.

Alongside Manfred’s keyboard and synthesiser skills, singers have always been an important part of his band. When Mick Rogers left, guitarist Chris Thompson joined and it is his vocal on their 1976 hit ‘Blinded By The Light’. After Chris left in 1986, the band took a break and Manfred recorded his first solo album, Plains Music, released in 1991. Noel McCalla sang on this record and then joined the band to tour. Manfred reflected, “In some ways you would imagine he [Noel] doesn’t have the right voice for the songs that Chris Thompson sang but Noel was so musical and with such good feel so that, even though it wasn’t quite the right voice for

the song, it worked. When Noel came for the audition to sing ‘Blinded By The Light’, he only had to sing one song and I said, ‘You’ve got the job.’ Same for Robert – he came to my house, he sang half the song and I knew he could do it. So I said, ‘Let’s go have a cup of tea.’” Chris Thompson re-joined in 1996 and then he and Noel were together in the band for three years. Manfred remembers, “That was probably the best vocal line-up we ever had when you heard them live.” You can hear them on the double CD Mann Alive, which was recorded during the 1996/1997 Soft Vengeance tour. With Manfred, Chris and Noel, this line-up also features Mick Rogers, Steve Kinch on bass and John Trotter on drums. Chris has described the band as a ‘democratic dictatorship’ so I asked Manfred what he thought of that. “Yes, I think that is pretty good. Really, a lot of decisions are made by consensus. I don’t like to move against the consensus. Everybody should feel they have some input and they are being listened to. On a minute-to-minute basis I don’t take myself so seriously that anyone has to treat me with respect or anything but ultimately it’s Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. Everybody knows that. There are decisions that only I can make. I think that is a very good description.” Manfred described a rehearsal principle they use as a band. “If a guy comes up with a bad idea and you explain to him why it’s not going to work, at first he’ll never believe you are right. He starts defending that idea and you possibly have a conflict. Sometimes he’s come up with a great idea and he’s explained it badly and you’ve misunderstood it because you are using words to describe music, which is never good. And some really good things happen when you listen to people properly. “I got that breakthrough when we were doing the single ‘Blinded By The Light’. It’s an extremely complex record, much more complex even than the album track. We were trying to simplify it to make a three-and-a-half-minute single and we had to cross-fade things. Chris Slade, our drummer, said, ‘Why don’t you play ‘Chopsticks’ over the cross-fade?’ It sounded ridiculous and I said, ‘Chris, you can’t do that.’ “But he kept coming back to it. I suddenly realised he’s a drummer, he’s not hearing chopsticks, he’s hearing the chords of ‘Chopsticks’. And in the end, even though he’d explained it badly, it was a real breakthrough moment in the record. I hope he reads this – it’s to his credit that we figured that out. We might have got there in the end but he was right and I was wrong. ”And the other thing is, if you’ve got me and the four guys and someone wants to change their part, or you want to change their part, then you must make sure that nobody else changes their part. So everyone stays the same and you isolate the one element of it and see if that works.” Manfred has released two albums that directly reference his native South Africa. The first, an Earth Band album in 1983, was Somewhere In Afrika. This gave Manfred a dilemma because it was a very political time in South Africa and he didn’t want to appear to be lecturing to people. “All through Somewhere In Afrika I was aware that this work is music. I kept saying, ‘Forget the politics, does this work as music?’” The second side of the album contains his ‘Africa Suite’. “I walked into a room with some African guys and I’m telling them what to sing. The

thing I remember very clearly is the opening line, ‘It’s not for me to say to you what you must do.’ I was asking them to sing freedom lines. It was such a paradox.” Apart from this, Manfred kept to his approach of recording good songs by including rearrangements of Bob Marley’s ‘Redemption Song’, ‘Nostradamus’ by Al Stewart, and ‘Demolition Man’ by Sting. He returned to South Africa for his !rst solo album, Plains Music. “I already had the idea of the North American Indian melodies and chords when I went to South Africa to visit my family. I met a guy who plays a hunting bow, an African named Smiler Makana. I liked the idea of that sound and he recommended two others. We rehearsed for two days and then recorded it in two days. I then went back to England and spent probably a year trying to finish it off, adding other musicians and singers.” This album also features the saxophone of Barbara Thompson who took time off from her own band to record with Manfred. This gives the album a special quality. Manfred told me he doesn’t normally listen to his own albums but: “It’s the only album I can listen to without getting irritated by the mixing or the production. Plains Music had something about it that really works. I don’t listen to it that often – maybe once a year.” Manfred Mann released his second solo album, Lone Arranger, in 2014. I suggested that the title is perhaps a good summary of his career. He explained that it was going to be called Manfred Mann The Arranger but his business associate Steve Fernie suggested Lone Arranger. “The play on words is really good. I like that. The bottom line is I managed to succeed because I have an ability to rearrange, to rethink, to treat everything as if it’s clay and you can remimble it around.” I comment that he must listen to a lot of music. “No, I’m not listening – I’m searching for a good song. People send a song through and I listen but that’s searching for a good song, it’s not listening.” As he chats to me from his kitchen at home, I ask him what he does to relax. At this point he seems lost for words, laughs and replies, “I’m not quite sure what the word means. I practise a lot, perhaps not enough. I play piano every day. I wake up in the morning and I go to try and solve a musical problem in my studio or practise and figure out how you should put your fingers. That’s the difference between being a classical musician and being an improvising musician. The classical musician knows what they are going to play and the specific fingering. As an improvising musician, you need to know that at any point in the keyboard your fingers may go in any direction. You don’t know what you are going to do next. It’s a different approach. So how do I practise this? These are the things I do all the time. “I’ve been playing an old keyboard, a Novation X-Station. It’s not really old but in modern terms it’s old. It’s not got the best sound but on the left hand controller you can bend notes and alter the filter with one movement. It’s not on two movements. Most of the modern keyboards are based on the Minimoog where you have two sliders and if you want to bend a note that’s an awkward motion. This is much easier. “Now I’ve got a Novation Peak, which is an analogue sound. I haven’t yet used it on a gig but I’ve been using it at home here and I’ll be taking it on the road. So I’m trying something new in order to get that kind of Moog-ish sound and to be able to control it easily with the left hand.” Even at the age of eighty-one, and having been prevented from touring for the last two years, it’s clear that Manfred continues to relish playing music and trying new things.

Looking back over the fifty years of Manfred Mann’s Earth Band, while the band are good musicians, they are also very aware of the need to entertain an audience. In the late 70s and early 80s, cartoons would be shown behind the band. Manfred explains: “Before we did that we used to do a slide show at the back of the stage and the funny thing is the slide show, which sounds kind of old-fashioned, has one enormous advantage over movies in that you can sync with the music. We had one moment when Chris Slade would hit a cymbal and Big Ben would come up.

The timing was much more dramatic before we had the cartoons. The idea was to try to create another level of entertainment. That was the time when bands like Floyd were spending fortunes and doing big shows. I thought, ‘How much of this can we do to give people another level of entertainment?’ So we did that and people really liked it and would talk about it. Then I realised that the economics really didn’t do it. People enjoyed the gig just as much without the cartoons. “The one requirement for a gig is whether the people at the back, not the people at the front, are moving their bodies physically when you are playing. Even if it’s just a !nger or just tapping their foot lightly. When their body is moving even slightly then you have captured their physical being. I got a quote from Count Basie: ‘As long as people are moving you have got them.’ In my view a gig is a physical experience. If people are sitting still, you haven’t got them. The thing that makes a successful gig is when the response at the end is better than the response at the beginning.” I spoke with Pete Dutton who has been the front-of-house engineer for the Earth Band for the last ten years. He told me, “Manfred is a joy to tour with – he’s friendly, very intelligent, learned, and a very accomplished musician. After ten years, I still find it a pleasure to do gigs with the band. The arrangements of the songs – all by Manfred – are amazing; he has a real knack for dynamics. I have to say that as I’ve been in this business for over forty years, this is one of the most enjoyable bands to work with. The band are very tight and the gigs are all good, with usually around 1,500 to 2,000 people, in most of Europe.” As someone who knew the music of Manfred Mann in the 60s, I had almost completely missed out on that of the Earth Band. In the process of preparing for this article, I discovered just what I’ve missed. I’ve had the opportunity to listen to their music, and watch videos of their live performances. The recently released Mannthology, on both CD and vinyl, provides an excellent and more detailed review of their music: a mixture of progressive and hard rock and haunting rhythms with plenty of groove. It’s not known whether Manfred will release another album but, even after sixty years as a professional musician, he still has the desire to perform live.